@ July 2003

Since the veteran Japanese battleship NAGATO sank on the night of 29/30 July 1946 at Bikini Atoll, strictly speaking, her "last year" covers almost exactly the time period from her last stand at Yokosuka in 1945 to her atomic funeral. However, to properly discuss it, some backstory is required. In truth, the last phase of NAGATO's career began on 23 November 1944, when she returned home to the Inland Sea bloodied from the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Nor had the return voyage been without incident --- en-route, on 21 November in the Formosa Strait, the battleship KONGO leading the formation had been torpedoed three hours after midnight. Losing speed and listing to port, she had tried to continue with the formation, only to fall out of line, capsize and explode after two hours with the loss of ComBatDiv 3, her master, and all but 337 officers and men aboard. Moreover, another division flagship and ComDesDiv 17 had been lost with destroyer URAKAZE which was torpedoed and sunk with all hands in the same attack.

Shaken by this disaster, the crew of the NAGATO had their own future to consider. Separating from the YAMATO, the NAGATO was scheduled to proceed on to her home port of Yokosuka, accompanied by the surviving three destroyers of DesDiv 17. They arrived at 1445 25 November. For the destroyers, the stop was only temporary. In three days they would sortie again with the new super-carrier SHINANO on a voyage nearly as disastrous as the one that claimed the KONGO. For NAGATO, however, the stay was to prove far longer, nearly permanent.

In a few more days came the last month of 1944, and as the next anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor rolled up, many Japanese had cause to reflect on the disastrous turn Fortune's wheel had made in the past three years. Even Yokosuka was no longer safe. The hapless SHINANO had been dispatched on her ill-fated maiden voyage to Kure precisely to avoid air attack, only to fall to a submarine. But that same danger from the air still existed, and the crew of NAGATO increasingly anxious for the ship's safety. The battleship was now secured to the Koumi pier with heavy lines that would take time to cast off, and worse, none of her boilers were lit. It was obvious she could not clear the dock on even reasonable notice, let alone emergency.

To help thwart this danger, NAGATO's commanding officer RAdm Kobe Yuji and the CO of the Yokosuka Naval Base had met on 4 December in order to discuss the possibilities how to protect the immobilized vessel. It was decided to paint the whole hull over to resemble the shore and buildings and to cover her main gun turrets with wooden scaffolding. Spurred by the danger of air attack, the work proceeded extremely rapdily. Only four days later it was completed. To test its effectiveness from the air Cdr Inada Susumu - the battleship's bosun --- commandeered a seaplane and personally made several overflights. When he taxied back up and reboard, he was frowning, and warned: "Skipper, our camouflage does not work. It can fool a pilot at higher altitudes but you can clearly see the ship from 3,000 meters (9,840 ft) and below." (1).

Given this, Inada suggested that the crew should start digging shelters at the nearby hillside in order to find cover against the air attacks. Upon warning of approach, they could troop ashore and wait out the bombing (the general idea was also done on some German capital ships in 1945). It was an unpopular decision but there was no fuel left for the NAGATO despite persistent rumors that she would be sent to a lone wolf sortie to the Southern seas. RAdm Kobe strongly opposed the idea, declaring that running away from an air attack would make the crew of NAGATO "the laughingstock of the entire world".

However, RAdm Kobe did not have long to concern himself with the matter. On 20 December 1944 a general reshuffling of command took place. Vice Admiral Kurita was reassigned to the Presidency of the Etajima Naval Academy, and Vice Admiral Ito Seiichi -- Vice Chief of the Naval General Staff --- took over command of the 2nd Fleet. On the same day RAdm Kobe moved on to assignment with the Naval General Staff. His place was taken by Captain Shibuya Kyomi, fresh from having brought his former command, the carrier JUNYO, home to Sasebo despite considerable damage from a spectacular three-submarine ambush on 9 December. With the arrival of the new skipper Captain Shibuya the camouflaging work was renewed with some of his suggestions, while the secondary guns and about half the AA guns were removed. In addition to a coal-burning donkey boiler installed direct on the pier, the 270-ton converted subchaser FUKUGAWA MARU No. 7 (formally assigned to Maizuru Naval District) arrived to provide the battleship with steam and electricity.

New Year's 1945 opened on a dismal year for the Imperial Japanese Navy. On that date, BatDiv 3 was formally abolished and the NAGATO re-assigned to join YAMATO in the reorganized BatDiv 1. However, with NAGATO so far north of the rest of the fleet at the Inland Sea, no opportunity to operate with YAMATO, CarDiv 1, or the others arose. The NAGATO remained in comparative isolation in Tokyo Bay waters.

However, on 9 January arrived a bit of company. The newcomer was a ship that like NAGATO, had pretty much faced and survived the worst the enemy had to offer. She was destroyer USHIO, the last survivor of the famed FUBUKI-class DDs. Like NAGATO, she arrived worse for wear, with only the port turbine operational, and like her, she never left that port again in the war. By this fluke that had the pair separated from the bulk of the fleet in the Inland Sea, they were not involved in the big raid on Kure on 19 March 1945. Further, both of these veteran `orphans' by necessity missed out on what proved to be the tragic "Last Sortie" of 2nd Fleet, when the legendary YAMATO and most of DesRon 2 sailed to their doom off Okinawa on 7 April 1945. Eleven days later, 2nd Fleet and DesRon 2 themselves were abolished, and the Imperial Navy was all but finished. The surviving capital ships would be carefully maintained and re-assigned to ad-hoc roles for the defense of the homeland against the imminent Allied invasion. It wasthis role only that the NAGATO could now look forward to; that and certain enemy carrier-air attack.

On 27 April 1945, Rear Admiral Otsuka Miki succeeded Captain Shibuya to command of the NAGATO. Although he had been serving in merchant ship duty since the war began, Miki had been the battleship's communication officer in the 1920's and was very familiar with her and a good choice. Miki continued the work of his predecessor, and added some touches of his own. In the following weeks the crew was tasked with erecting two spotting stations at Fujisawa-Enoshima and Oiso. In case of an allied landing, the stations would provid NAGATO's main caliber batteries with fire control information. As the summer came, the tempo of enemy activity increased. The Battle of Okinawa was in full bore, and raids on the homeland by aircraft were frequent. On 1 June the NAGATO was assigned with HARUNA, ISE, and HYUGA to the Special Coast Guard Fleet. On 22 June came the dire news of Okinawa's fall. It could not be long now. The homeland itself was the enemy fleet's next target.

This squadron would have the task of repelling a close approach to the home shore by enemy surface forces. Kure had already been attacked on 19 March, but the fleet had gotten off relatively lightly. It was clear that more of the same was imminent, and that this time they would not be so fortunate. For both the fleet in the Inland Sea and NAGATO that testing came in July 1945. However, the NAGATO would emerge from it more fortunate for reasons seen in the dramatic story to follow.

The Japanese were quite right in their projections. In fact, the expected sortie of the American fast carriers had begun the very first of July, as the day opened on the awesome sight of TF 38 leaving Leyte Gulf, on the prowl once more. It was fully replenished and rejuvenated, reinforced by three carriers. At long last, this was the sortie where the coast of Japan would be, and would remain the target. The armada filled their tanks to eastward of a now subdued Okinawa and headed north toward Honshu, bound for Tokyo, which they had not visited since mid-February. Hidden by a weather-front, the carriers reached launching position 170 miles southeast of Tokyo before dawn on the 10th.

The raids savaged the airfields, meeting almost no opposition, since IGHQ orders to conserve aircraft remained in force, even now. This was still not the epic battle `Ketsu-Go'; they must wait. Even waiting was costly - Nearly 110 planes were reported destroyed on the ground.

Even these raids were but overture to Admiral William "Bull" Halsey, whose TF 38 effected a rendevous with the carriers of the British Pacific Fleet and then moved in for the kill. This July he had determined to go after the last surviving capital ships of the Imperial Navy full-bore, and as the former-flagship of Yamamoto at Pearl Harbor, the NAGATO was a primary prestige target among these. TF 38's strike against Tokyo on July 10 had revealed some worthy targets after the photographs taken were processed, among the most interesting, to Halsey, was the presence of the NAGATO, found moored in Yokosuka Naval Base.

The reconnaissance revealed a challenging picture. The former flagship of Combined Fleet was moored beside a pier amid a formidable defensive network of anti-aircraft in a difficult anchorage position surrounded by mountains. It was a challenge analogous to that faced by the Royal Navy carrier planes when attacking German battleship TIRPITZ in her confined Norwegian fjord hide-outs. Nevertheless, Halsey wanted to try. He wanted the NAGATO, the last symbol of Japanese supremacy as the largest battleship in the world (since YAMATO sank). It was from her bridge that Yamamoto had directed the attack on Pearl Harbor. There would be much obvious symbolism derived from destroying her, especially in a harbor. On the night of July 16, the joint carrier task force moved southwest, to be in position for dawn strikes on Tokyo area.

They were up against a rather difficult and well obscured target, that was if anything, a tougher nut to crack then was envisaged. By this time the NAGATO's complement had been reduced to 967 officers and men, but it didn't matter. Her greatest reliance would be placed not on her own defenses, but on the elaborate measures taken aboard and around her, the aggregate results of work extending from December 1944 to the present. As she had been throughout summer, NAGATO was tied up with her bow facing northwest at nearly right angles to the harbor entrance with starboard side against the pier and dock where stood the big yard crane of Yokosuka. This was the same crane near Komi Bay adjacent to the great `YAMATO-dock' most recently occupied by the ill-fated SHINANO. Across the east loch to port, the destroyer USHIO was secured stern-to to the Navy Yard Pier, in position to cover NAGATO with defensive fire from her 25-mm as best she could.

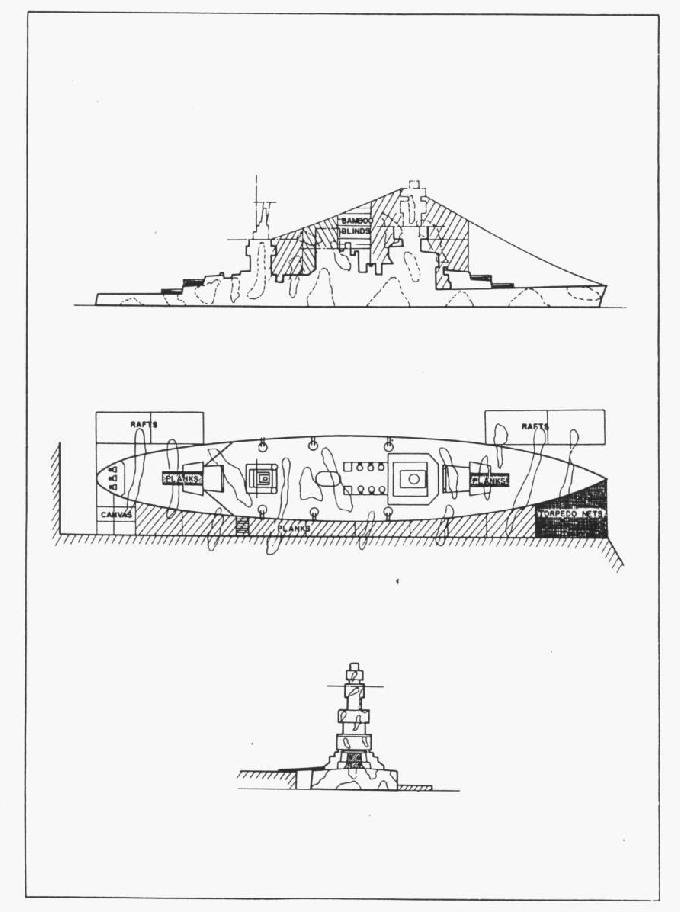

In another parallel to the TIRPITZ, the Japanese preparations were as extensive and long-term as the Kreigsmarine's in Alten Fjord. NAGATO's rangefinders and searchlights had been moved ashore and installed on nearby Okusuyama mountain, and other fragile equipment moved before camouflaging. The camouflage was arranged to obscure the ship from both the sides and from overhead. To break up the lines as seen from above, the 16in gun and the turrets were covered with planks. (see diagram) The secondary armament had been relocated to protect the Yokosuka piers from landing crafts. Other planks, torpedo nets, and canvas were used to cover up the space between the starboard side and the pier. One catapult and the AA guns on the starboard side side had been removed for that purpose and installed onshore atop the adjacent Urayama Mountain, so that NAGATO might `blend' into the wharfs and warehouses in an unbroken line. To round out the effect, rafts were moored at the port ends of the battleship to alter the shape. All of the conglomerate of dock, battleship, and rafts, was covered in dazzle painting of black, brown, grey and white to form a single continuous pattern.

To obscure the profile when attacked closer to sea level the NAGATO'S sides were also covered with the camouflage dazzle painting. Helping to make her profile difficult to see against the background of Yokosuka's hills, dazzle painted bamboo screens were hung tent-like between the mainmast and pagoda, and extended forward in a slant like a slope from the pagoda foremast.Potted pines and cryptomerias were set all about her upper decks.

To complete the procedure, even the upper third of the stack and mainmast were removed, to facilitate the draping of these camouflage screens. It it had even been planned to cut down the topmost portion of the massive pagoda foremast. This however would have made preparation for a final sortie (ala YAMATO) too difficult and was aborted. The NAGATO retained the profile appropriate to her stature.

To make their runs against her, any torpedo planes would have to make their low approach from the port side, from the direction of the harbor entrance, exposed to a murderous semi-circle of flak on land and sea. For this reason, Halsey's planners had ruled against the use of torpedo planes. Again like the attacks on TIRPITZ, the best hope was that at least NAGATO might be gutted by fire and her waterline torn open in places by concentrated bombing. Though torpedoes would doubtless be more effective against a Japanese warship, the likely cost in lives and planes did not justify the risk. After all, NAGATO was assumed to be too damaged to sortie soon. Actually, of course this was mistaken. The majority of NAGATO's Leyte damage had been repaired. Her problem was the absence of fuel, not damage. She was incapable of sailing far, all the same.

All of this did not deter "Bull" Halsey, who after an abortive foray on 17 July, turned again to the attack on 18 July. Once again inclement conditions interfered with morning flight operations for TF 38, but by the afternoon of the 18th weather was clear. Aircraft commenced launching from USS ESSEX, RANDOLPH, YORKTOWN, SHANGRI-LA, and BELLEAU WOOD.

The NAGATO was ready and waiting for them. They had sighted the small swarm of carrier planes that appeared over Yokosuka briefly on the 17th, and when one of enemy fighters suddenly doubled back and flew over the FUKUGAWA MARU at masthead level, they were certain the NAGATO had finally been spotted. A full air-raid was now expected at any moment. Actually, what the Japanese did not know is the fliers had already `spotted' the NAGATO, and were just taking final looks. In fact, if not for the bad weather, she would be under full attack already. As it was, Otsuka was given one more day to further brace his ship for battle. He recalled Ensigh Takashima Sekio and his men who had been supervising further defense construction at Enoshima.

During the forenoon of July 18, an air warning standby was received from Yokosuka Naval District HQ. "All hands, finish your lunch now!" the loudspeakers announced all of a sudden. "Air warning, first state of readiness! Prepare for the air engagement!" Moments later Yokosuka district HQ issued an overall readiness alert. The sailors of the 7th Division manned their 25-mm AA guns on the nearby hillside. Looking anxiously below, they could see their ship just beside the big yard crane and were pleased that it was indeed, difficult to discern.

Manning their places on the bridge at the time of the attack were eighteen officers and enlisted men, including Rear Admiral Otsuka Miki, his executive officer Captain Higuchi Teiji, radar officer Ensign Shimizu Kenjiro, staff navigator Ensign Takashima and Quartermaster Chief Fukuda Yasushi. Together they listened tensely to each updated report as it came crackling in over the radio. After 1500, the NAGATO received a report about 250 carrier planes raiding the Yokosuka area. In the foretop, the radar crew provided regular reports on their progress while Ens Shimizu plotted it on the chart. Navigation officer Takashima stood by the chart table forwarding Otsuka's orders to the appropriate battle stations. The tension was palpable.

Then about 1530 came the first visual contact with the raiding aircraft. Ensign Takashima watched how the formation split up into two- or three-plane sections, each streaking towards their targets within the base perimeter. Far away the AA batteries were hammering incessantly but no plane was seen falling yet. Then the 25-mm guns at the hillside joined the fray as well. However, the guns of NAGATO and USHIO remained silent. There were no aircraft heading for her yet and firing at distant planes would only advertise the location of the stationary battleship. The Japanese could not know that the Americans were well aware of and had been carefully briefed on NAGATO's position and the defenses. They were merely seeking the best moment and angle to attack.

Some ten minutes later a formation of sixty planes was sighted heading westwards. To the NAGATO it seemed they had failed to sight them. "See, our camo still works," commented somebody on the bridge. Otsuka said nothing, watching suspiciously and intently. Sure enough just then the entire group started a turn for an attack out of the sun.

"All hands, don your helmets and gas masks!"

Takashima and other younger officers were reluctant to do so: they were still firmly convinced that NAGATO could not be spotted. "Are the Americans really going to attack us?" Takashima whispered to Shimizu, who was standing next to him by the chart table. Shimizu shrugged "What's the use of a helmet against a bomb hit anyway?" he grinned. Then a further warning came. "Three incoming aircraft dead ahead!" one of the foretop lookouts shouted through his voice tube. CO Otsuka looked, then calmly ordered: "Commence firing!" . What ensued next was a fast and furious anti-aircraft action lasting barely twenty minutes. Aircraft mostly from USS RANDOLPH and USS YORKTOWN pressed home their attack in the teeth of fierce AA fire, judged among the worst TF 38 fliers had encountered to date, even compared to Cape Engano!

A group of planes hurtled toward NAGATO's port bow, arcing in over the harbor entrance where there was space to maneuver. On the BB Ensign Takashima pressed the intercom button to relay the order to each battle station to open fire. But in the next moment the entire bridge was engulfed by fire. Two 250 kg bombs dropped by the attackers had hit the bridge squarely. Ensign Takashima was hurled to the deck and was insensate for a brief time.

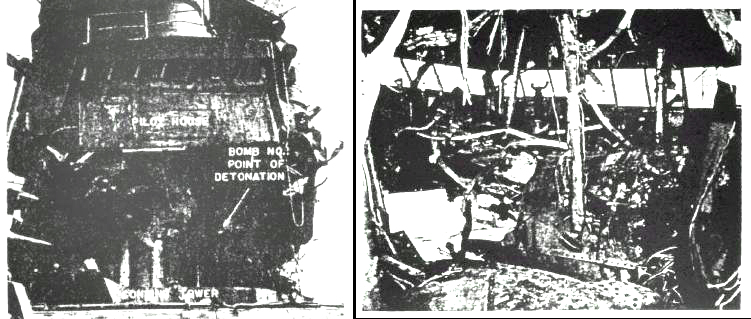

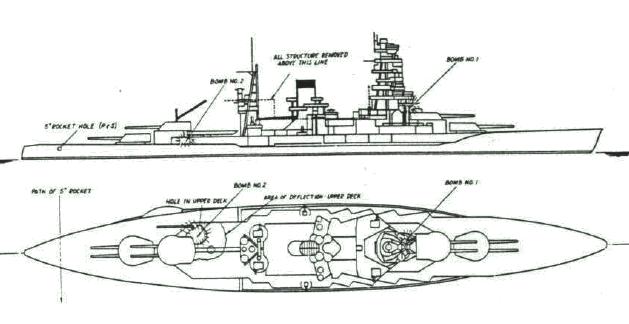

In truth, it appears it had been only one 500-pound GP instantaneously-fused bomb, but it wreaked great havoc. It hurtled in on an angle broad on the port bow, slanting down at 45 degrees and detonated at 1552 (the compass bridge clock was found stopped by the blast) against and just below the deck of the pilot house and above the roof the conning tower. The pilot house was utterly demolished, and a hole 12 to 15 feet in diameter torn in its deck. Fragments from the blast tore thru the next two levels of the pagoda above, but the conning tower roof below held firm and the personnel inside uninjured.(2) Unfortunately, the same could not be said for Nagato's master and many others who had been in the bridge area at the time.

Takashima later described what he saw. After regaining consciousness, Takashima saw that the forward section of the bridge was heavily devastated with traces of blood visible everywhere. The bomb had apparently penetrated the secondary caliber reserve plot at an oblique angle, exploding on the conning tower roof and demolishing the compass bridge. Loose wires hanging down from the overhead looked strangely incongruous, just like somebody's leg jammed between them.

"Skipper? Exec? Shimizu? Where are you?"

There was no answer. CO Otsuka, XO Higuchi and the radar officer Shimizu, all twelve sailors standing in front of the chart table were dead. In contrast, navigator Takashima, QMC Fukuda, a petty officer and three other sailors standing behind the table had been spared.

There had been a "mantlet" rope screen separating the compass bridge and the navigation area. Prior to the attack many sailors had made jokes about the efficiency of such flimsy device, resembling the entrance to a typical Japanese-style inn. Nevertheless it had saved the lives of those located at the rear of the bridge.

Now that both the CO and his Executive Officer were dead, somebody among the division chiefs having the rank of a Commander should have taken over the command. In theory it should have been Cmdr Okuda Takeshi, Chief of the 8th Division (main caliber artillery/ electricity). But Okuda's battle station was in the plotting room belowdecks and nobody on the bridge was sure whether Okuda himself was still alive. As a matter of fact, Commander Okuda had been on his way to the bridge when the blast of the explosion caught him frontally. His face was badly burned, but he staggered on up the ladders.

Ens Takashima had no idea about Okuda's plight and decided to take over the command of the ship himself. He was well aware that no reserve ensign with a rather shallow background in navigation had yet commended a battleship. What about those AA guns–none was firing!

"AA guns number one and two, why aren't you firing?" he inquired via the voice tube.

"There is no ammo. The hoists are all knocked out."

Ens Takashima dashed to the galley where he discovered the gathering of some very scared ratings.

"Are your provision elevators still moving?" Takashima asked.

"Yes, indeed," one of the cooks reported.

"Then pass the ammunition from below and fast!" Takashima shouted. Once the AA guns had received the first shells, he returned to the bridge, only to meet Cmdr Okuda whose face was horribly burned. To say that Takashima was relieved would have been an understatement.

"So you are alive, Okuda! Both the skipper and his executive officer are killed. What are your orders, sir?" Just then the lookouts reported the second wave with some 40 aircraft approaching from astern. "Takashima, you stay here," Okuda decided. "I must return to the plotting room."

The enemy bombardment continued, and the converted minesweeper HARUSHIMA MARU which had been moored next to the NAGATO received a direct hit and broke in two. Nevertheless, despite having lost most of her command officers, the NAGATO's batteries and the surrounding AA of Yokosuka and on the nearby destroyer USHIO put up a furious barrage. Because of their effort, only two further hits - a second bomb and possibly a rocket - were scored by the marauding aircraft.

The second bomb was also a 500-pound `non-delay' fuse, and like the first hit had hurtled in from an angle off the port bow, smashing into the side of the raised 01 deck aft of the mainmast on the port side. It penetrated nearly five feet toward the centerline before exploding against the base of No.3 barbette. The barbette was gouged, but not distorted and the turret above it undamaged. However the bomb had detonated in the vicinity of the lightly plated officer's lounge on the port side and a hole nearly 12 feet in diamter blown in its ceiling. Though there was no fire, the blast killed about twenty-two men and knocked out four 25mm on the upper deck.

The possibly third and last hit was apparently a dud 5-inch rocket that struck NAGATO's fantail at nearly right-angles on the port side four feet below the main deck at the Admiral's cabin. It tore right through the stern and out the opposite starboard side without detonating. Incredibly it had struck nothing apart from Admiral Ugaki's former table, gouging a groove two inches deep and eight inches long in its top! The missile had exited at a slightly higher elevation then its entry point. I say `possibly third hit' because some question exists whether this damage was even inflicted on 18 July, for supposedly no 5-inch rockets were employed. Because of this, it is possible this was a 5-inch hit from the Battle of Samar or subsequent air attacks after the Leyte Gulf battle. Given its trajectory, it is not impossible it was Japanese in origin. There was also several near-misses off the port side, which piled up wet sand on the deck, but seemingly did little damage.

By 1610 the attack was over. Then at the direction of grim and bandaged Commander Okuda, now acting skipper, the sailors started to remove the bodies. As they entered the compass bridge, there stood the clock hands frozen at 1552 hours, capturing the exact moment of its destruction. In the attack, between the two bomb hits, the NAGATO had lost 35 officers and men. Looking around, it could be seen that in addition to the blasts on NAGATO,other warships in the harbor had been hit and damaged. The scene was a tableau of smoke and destruction.

Warped against a dock just to port and across from NAGATO, the unfinished hull of the Matsu-class destroyer YAEZAKURA, was bombed and broken in twain. By the end of the raid only her forepart and a portion of the stern projected above water. She had been launched 17 March that same year, but her construction had already been suspended in June when 60% complete. In identical state was sister ship YADAKE, but she was not hit. Also damaged were the training vessels FUJI and KASUGA, while the target control vessel YAKAZE was hard hit. The old destroyer was left smoking and leaning to starboard at a dock.

The biggest destroyer present, veteran USHIO, somehow escaped harm. She was secured stern first to the Navy Yard pier near Komi Bay, just across from the battlewagon where her guns gave effective cover.Miraculously, FUKUGAWA MARU No. 7 had escaped any damage despite of numerous near misses. So had USHIO, whose fierce gunfire was credited in limiting the damage that day.

Finally, the Yorktown planes sank I-372, just as she was preparing to sortie from dock. Though the submarine was completely wrecked, the bright side was that Lieutenant Shingo Takahashi and his crew were still ashore and no lives were lost. The I-372 had been converted to carry gasoline as a tanker and was ready to sail for Singapore, but a near-miss ruptured her starboard midships gasoline tank and the big submarine succumbed to the inrush of water.

On the Allied side, the Japanese fire had been ferocious, and had exacted a heavy price in return. No air opposition had risen, but the AA fire had been among the strongest yet experienced. While planes from the USS YORKTOWN and RANDOLPH had gone after NAGATO, the others had attacked the airfields in the Tokyo area. In addition to the damage infliced on Japanese ships in Yokosuka Harbor, forty-three planes were claimed destroyed, with damage to seventy seven, and even a number of train locomotives. The cost to the Allies had been fourteen planes and eighteen fliers that day, most of them over Yokosuka.

The most disappointing thing to TF 38's fliers was the only moderate damage to NAGATO. However, if Halsey had known, he might have found some consolation in an ironic fact. For the bridge section of NAGATO had been demolished. Considering that was the spot Yamamoto had given the Pearl Harbor orders from, in an oblique way, Halsey's fliers achieved the revenge they had been seeking after all.

That hardly compensated for the fact that bombs alone had seemingly been unable to sink a well-defended and camouflaged warship. It did not bode particularly well for the planned strikes against Kure scheduled soon. Like Yokosuka, it was envisioned that torpedoes could not be used safely, and that the survivors of the Imperial Navy would have to be sunk by a concentration of heavy bombs, rockets, and bullets. If NAGATO and the March raid were any indication, it could prove frustrating. (That was not quite how Kure turned out, but that is another story).

The saddened but still determined crew of NAGATO set about removing the bodies, taking stock, and commencing what repairs they could to their ship. Despite the two bomb smacks, that damage proved relatively light, as the later U.S. analysis stated: "As nearly as could be determined, there was no internal damage or flooding....NAGATO's two bombs had little effect on her fighting efficiency. However, they serve very well to illustrate the effects of small bombs, instantaneously or "non-delay" fused, on capital warships."

However, the enemy did not have to know this. To try to mislead and convey the impression the NAGATO had "settled at her moorings" some of the battleship's ballast tanks were filled with water to cause her to sit deeper. The compass bridge and pilothouse were also left unrepaired -- by necessity rather than design -- but this only added to the picture of a derelict by the dock. There was still the matter of the deceased skipper. Otsuka was duly posthoumously promoted to Rear Admiral, and Captain Sugino Shuichi assigned as commanding officer to replace him. However, at that time Sugino was at Port Arthur, Manchukuo. Given the present conditions, it would take some time for him to arrive. To cover the gap, Rear Admiral Ikeguchi Masamichi was recalled from retirement and assigned temporary duty as the NAGATO's Commanding Officer.

Despite the disaster to her compatriots at Kure that week, by the end of July 1945 the NAGATO herself was once again ready for action. Even though the war was rapidly rushing to its atomic conclusion, at this time CombinedFleet still entertained no notion of surrender, and certainly not of conserving its warships if an opportunity to strike a blow offered. For NAGATO this opportunity seemed to appear at the very first of the month.

Around midnight of Aug 1, the Yokosuka Naval District received an alarm from lookouts stationed on Izu peninsula about a major enemy convoy sighted off Ôshima Bight, heading straight for Sagami Bay. This was the opportunity they had been waiting for! An enemy fleet close enough to reach despite the fuel crunch. The Yokosuka Navy Yard became a flurry of activity. The Staff Gunnery Officer (a Cmdr Hatakeyama) rode to Nagato on his bicycle to give her CO the order to sortie immediately and to intercept (what was thought to be) the landing force. With luck, they could be well on the way before sunrise.

However, when Hatakeyama got to NAGATO, he heard crushing news. He was remined that the BB had enough fuel to reach Sagami Bay only, her boilers were not lit and all propellant charges were stored in underground tunnels. This would greatly delay things, and prevent immediate sortie. Still, Ikeguchi and his crew were determined to make the best effort. Reloading of propellant charges started immediately and lasted until daybreak, 2 August. Early in the morning a fuel barge arrived as well and the water from ballast spaces was pumped overboard. Therefore, despite the delay, Ikeguchi would soon be ready to take her out.

However, as the morning dragged on, there was only frustrating silence from headquarters. No orders to sortie arrived. No course to intercept the enemy sent. A few hours later, came the deflating truth: the sortie was cancelled. Not because of change of heart, but for the simple fact it had been a false alarm. There was no enemy close enough to engage.

After the abortive 2 August sortie possibility, events rolled forth rapidly to their awesome and unexpectedly sudden conclusion as four days later Hiroshima and then three days after it Nagasaki were both annihilated by atomic bombs. At noon 15 August, Admiral Ikeuchi assembled the whole crew on afterdeck to listen to the Emperor's fateful live radio transmission of his Imperial Rescript that calls for an end to hosilities Following the surrender announcement it remained only for NAGATO to prepare for the melancholy reception of the Allied fleet in Tokyo Bay itself. Stationed as she was at Yokosuka, the NAGATO would occupy a ringside seat to this historic drama.

Five days after the surrender, Captain Sugino Shuichi at last arrived to assume command. He was an officer of considerable experience and distinction, with more than a few close calls to his record. The closest easily being when his last command, CVE TAIYO, and been blown apart and sunk by submarine attack with the loss of all but 300 or so aboard. By some miracle, Sugino himself had been among those rescued. Now he was preside over the surrender of Japan's last operational ship-of-the-line.

That day was only twelve days later, but before then, there was one thing Sugino could do at least. With surrender imminent, he had a sudden recollection of the fact that a lifeboat of the Czarist Russian battleship OREL was still displayed at Etajima Academy. A lasting reminder of the Tsushima victory and Russian surrender half-a century ago. Now the Japanese fleet was the one doing the surrendering, and Sugino did not want to leave `trophies' for the Americans to exhibit in Annapolis. He gave orders to remove the chrysantheum crest from NAGATO and had it burned on the afterdeck. It took nearly all of a day for the large crest to born, its pyre a mute testimony to the reality of defeat.

It was unknown precisely what would happen when the Allies arrived to occupy. Some expected a final furious attack, others a humiliating confiscation. Whatever would transpire, NAGATO would not meet it like a maru skulking and seized at dock side. She would face it in open water. Prior to the end of August, the battleship shoved off from the pier, and moved to a spot outside the harbor entrance, off the Azuma Peninsula. There, still inside the main breakwater near where Sagami joined Tokyo Bay, the NAGATO was swung around so that her bow faced south and back toward Yokosuka Harbor. From this position, her port battery held a commanding view of the sea.

On 29 August 1945 the USS MISSOURI (BB-63) and the IOWA (BB-61), in company with numerous minesweepers and destroyers, entered Tokyo Bay and moved toward Yokosuka Ko. The MISSOURI was the batteship chosen to host the signing of the instrument of surrender, and from the IOWA flew the flag off Admiral William F. Halsey's Third Fleet.

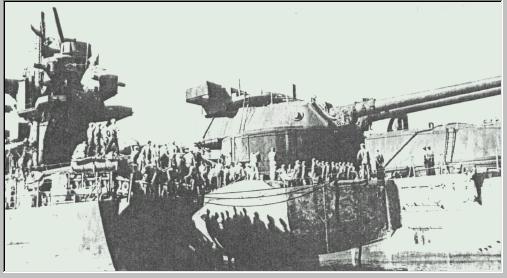

As the Missouri rounded the peninsula exiting Uraga Strait and entering Tokyo Bay, she was thus confronted by a momentarily disconcerting sight: there, port broadside commanding the approaches, loomed the ominous bulk of battleship Nagato. In perfect position to `cap the T' in ambush. With bow facing south into the harbor, Nagato seemed poised to dash back inside after raising whatever mischief she might. Yet after a few seconds of wariness, it was realized that Nagato's great 16in gun turrets were trained fore and aft. She was not contesting the entrance into the approaches of Tokyo Bay, but only bearing witness.The American and Japanese battleships eyed each other warily as the Missouri moved slowly past Nagato. Onlookers could see that the Japanese battlehips's pagoda foremast was chewed up, with the pilothouse bridge completely wrecked. Nevertheless, she still looked menacing and remained manned, but there was no incident and soon after at 0925, Missouri's anchor shot down and splashed into the waters of berth F71, Tokyo Bay. The IOWA pulled up to port alongside her.

At 1400 Admiral Nimitz arrived in two seaplanes that landed and taxied up to the battleship SOUTH DAKOTA, which Nimitz then boarded and broke out his flag as flagship. The SOUTH DAKOTA proceeded to take up position to port of NAGATO. For a long and portent filled evening, American and Japanese battleships spent the night in close company and surreal peace, their crews contemplating what the morrow would bring. One can almost imagine the ghost of CinC Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku hovering around NAGATO's bridge as his still living opposite number on "SoDok" rested only hundreds of meters away to preside the next day over the transition to a new era. The schedule called for the formal occupation of Yokosuka Naval Base after dawn on the 30th.

It began on schedule at 0900 as Real Admiral Robert B. Carney - CoS Third Fleet - took the cruiser SAN DIEGO and headed toward the Yokosuka pier to receive the surrender from Vice Admiral Totsuka Michitaro, commander Yokosuka Naval District. At the same time, a boarding party in landing crafts was moving to secure the official surrender of the NAGATO. Navy Underwater Demolition Team 18 executed the task and was led by the battleship IOWA's executive officer, Captain Cornelius W. Flynn. This "capture of NAGATO" was purposely dramatic and "symbolized the unconditional and complete surrender of the Japanese Navy".

The vessel carrying Team 18 swept alongside Nagato's port side, amidships aft. Lines were thrown with hooks as if in boarding and then Captain Flynn and his officers mounted to the deck. Waiting for them on the quarterdeck was skipper Captain Sugino Shuichi. There then followed an incident which Japanese descriptions do not confirm, but fail to clearly deny.

According to Admiral Halsey, after Captain Flynn's boarding party was received aboard with perfunctory courtesy, Captain Flynn directed Nagato's captain to lower his colors. With a grimace, the officer gave the order to a sailor, but the American curtly snapped:"No. Haul them down yourself!" Whether Captain Sugino actually did, or one of IOWA's team did, the NAGATO thereby passed ignominiously into captivity. In any event, the NAGATO's flag did end up at Annapolis.

There was another incident involving a flag soon after, one more amusing. Admiral Halsey transferred his staff and his person to the Yokosuka Naval Station, and at 1045, Halsey witnessed a proud moment in his career. His four star flag was raised aloft, the first United States Navy Admiral's flag to be broken over Japanese home soil. However, it didn't stay long! To quote Halsey:"Chester Nimitz gave me hell for breaking my flag ashore in the presence of a senior officer and ordered me to haul it down!" Yet a Japanese could recognize that given the prominent role Halsey had played in the defeat of the Emperor's Navy, it was perhaps appropriate he was the first. On 7 December 1941 he had been aboard USS ENTERPRISE as she numbly entered the still-burning Pearl Harbor. Bearing witness to the war's start, he was also there to do so for the conflict's finish.

For the NAGATO the official surrender of Japan that followed at 2 September 1945 aboard USS MISSOURI was something of an anti-climax. The proceedings took place at some distance to starboard from her, and her crew was already in a state approximating house arrest. In fact NAGATO no longer belonged to the Imperial Navy but it was not till 15 September that she was formally removed from Combined Fleet's Navy List. There was one ironic note: Captain Sugino and his men were repeatedly questioned about the whereabouts of sister-ship MUTSU during the surrender as well.

Captain Flynn, the XO of IOWA who had first boarded NAGATO now received command of her. Inspecting the roughly-handled but still stout battleship, her new American owners found that 918 16-inch shells were still aboard, and the turrets were operable, as were all main engines and boilers, though only one boiler appeared in use. In the small arms magazine were found twenty-five rifles and six pistols. The three direct hits on July 18 were mentioned, but of further interest, the captain reported 60 near-misses had opened holes in the double bottom fuel tanks and had let in 2,000 tons of water seepage.

NAGATO would remain under the "service" of her new masters for almost another year, before meeting her final appointment with destiny at the atomic tests of "Operation CrossRoads" at Bikini Atoll a year after her last stand at Yokosuka. It is not intended to go into the details of that operation at length, but a short summary of NAGATO's role in it will be given with excerpts from the relevant chapter of the author's unpublished manuscript "Total Eclipse".

After NAGATO was selected (along with brand-new CL SAKAWA) for participation in the test, preparations were made to get her ready for a final voyage. On 18 March 1946 the two ships got underway, bound for Bikini via Eniwetok. Manning NAGATO was approximately 180 U.S. Navy sailors now under command of Captain W.J. Whipple. At the time of sailing, NAGATO had four boilers operable and apparently the use of her two outboard screws only, for a speed of some ten knots. Her turrets were no longer operable, apparently from lack of maintenance. For more complete details of the journey, see the excellent trom prepared by Bob Hackett on our CombinedFleet site:

Nagato' Tabular Record ( TROM)

At the time of the first A-bomb explosion dubbed "Able" on 1 July 1946 the NAGATO's machinery was in the following condition: Turbine No. 1 was the operable shaft, Turbine No.2 was out of action. Turbines No.3 and 4 were not in use, but could be started with little difficulty. Of the ten boilers, No.1, 3, 4, 8, 9 and 10 were not operable prior to the test. Boilers No.2, 5, 6 and 7 were operable before the test and showed no damage after it.(3)

The account that follows captures the event:

"...Aiming point was none other than the veteran battleship Nevada, whose breathtaking sortie during the attack on Pearl Harbor had stirred the imaginations of all present. She was painted an ungainly red and orange, to aid the bombardier. Keeping her close company, the great Nagato rode off Nevada's starboard bow. The former enemies would face the wrath of the atom together.

At precisely thirty-four seconds past 0900 the moment came. The 21 kiloton bomb "Gilda" detonated at 500 feet above sea level with a brilliant and grimly familiar flash. The awesome process of fission took place. An amount of matter scarcely greater than a dime's weight was annihilated---but this produced an energy release calculated at 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 ergs; nearly akin to 20,000 tons of TNT! From the detonation center, a spherical shock wave spread outward at about 3 miles per second, striking the water before one second has passed.

In the midst of all this avante-garde and cutting-edge technological brilliance, human and mechanical error still remained. Poor Nevada had been the bulls-eye with Nagato closeby to share her fate---but the bomb missed! Instead of detonating directly over the Nevada as the test required, the bomb exploded 1,800 feet to the west of the Pearl Harbor veteran, almost over the light carrier Independence. The carrier's flight deck was destroyed, the stern chewed up, and the island smashed. Six hours after the test she was still ablaze, looking rather like her ill-fated sister Princeton had when she went down off Leyte two years before.

As for Nagato, the bomb exploded 1,640 yards off her port quarter. She merely suffered "insignificant damage" to her superstructure, some shock damage to the (already inoperable) main turrets, and some leaking valves were sprung. The main battery rangefinder on the foremast was disloged and communications partly disrupted. That was all. Machinery and vitals remained nearly intact. Companion Nevada was in about the same shape, except the superstructure damage was severe and the funnel crushed.

As a matter of definite interest, her American captors found something positive to say about the Nagato's performance. To their suprise, the boarding party found that inspection of the four operable boilers "revealed no damage whatever" even though the boilers on the U.S. ships at comparable ranges had been shattered or failed. The same went for Japanese battleship's better reinforced stack. The conclusion was:"It is recommended that the construction of boilers and uptakes of the Nagato be studied with a view to...incorporating some of their features into the design of our vessels in order to make them more resistant to blast pressure." The praise of NAGATO's boilers was well-earned. In fact, after the test the NAGATO was re-boarded and No.7 boiler brought online. The boiler was operated for thirty-six hours before being shut down again, and showed no sign of damage. Nor did the others.

NAGATO's comrade SAKAWA was far less fortunate. The blast reduced the lightly constructed superstructure to a shambles, and the once trim cruiser was reduced to little more than a floating junkyard. Only the bridge and gun turrets remained as definite landmarks. A large fire was started on her fantail and the hull fatally gashed aft. Though she lasted the night, after 0900 the next morning she keeled over to port and began to sink and by 1042 had gone to the bottom. The remaining ships were then carefully examined and prepared for the next test.

At 0835 25 July 1946 the second bomb, code-named "Baker" was detonated from a position slung beneath a landing craft. Intended as a "shallow water shot" at 500 feet it subjected the guinea pig fleet to the full force of water compression and shock wave. The venerable USS SARATOGA on one side, and the NAGATO on the other, at 950 yards each were among the closest to the bomb, with the exception of the hapless USS ARKANSAS only 500 yards away.

"...This great avalanche of water and spray swelled outward, slamming into Nagato's starboard broadside like a tidal wave; but a wave like few before; 300 feet high, several million tons of water, moving at more than 50 mph. As the cameras rolled, the whole form of the Japanese battleship was swallowed inside the obscuring envelope of destruction.

The venerable battleship Arkansas was flipped to port like a pancake being turned by this blast, smashed into the water and sinking within 60 seconds. The great carrier Saratoga, only 500 feet away, had her stern raised forty-three feet, and huge stack laid flat across her flight deck by the cascade.

Yet as the spray and cloud dissipated, the Nagato emerged, seemingly triumphant over the atom. Like an imperturbable mountain, she floated still, nearly on an even keel, her great pagoda and gun turrets showing little impression from Baker's fury. Only a two degree list to starboard showed that she had just faced the most terrible form of the atom bomb's power; the use of an undersea pressure wave.

Aft of the Japanese warship the venerable Nevada, not to be outdone, also rode out the wave, though her stack was crushed and masts bent. Other than that, like her Japanese counterpart, the survivor of Pearl Harbor seemed equally unimpressed. And both of these battleships had been less than 1,000 yards away. However, the appearance of battleships being atom-proof was deceiving. The billowing spray of the bomb had coated them with an invisible and lingering death..."

This time the aftermath was quite different from the first test. Though once again the NAGATO appeared to be floating almost normally with minimal damage, she and the other target ships registered as dangerously radioactive. The upthrown column of water had deluged the decks with contaminated seawater, making any thought of boarding to inspect the damage or check the health of the animals aboard out of the question. In fact, it was not possible to approach closer than 1,000 yards. After the test, the NAGATO showed a 5 degree list to starboard, but little change of trim beyond that. She did not appear to be sinking. An attempt was made to wash down the NAGATO and other vessels with fire hoses and rinse away the radioactive coating, but to little avail.

"It was the volume of this high radioactivity setting their gieger counters chittering frantically that amazed the Americans when they re-entered the lagoon. They had not expected such high radiation levels, since `Able' had been so relatively clean, but they had reckoned without the effect of irradiating water, as the underwater shot had done.

Salvage efforts were frustrated, and crews could not approach to re-board the vessles to stop flooding and study damage. The great water spray cannons of fireboats and tugs were turned on the target ships, in an attempt to `rinse' them clean, but to no avail. Unable to re-board her, the sailors were forced to watch sadly as the gallant Saratoga slowly settled from her wounds, and seven hours after the blast, she slipped under stern first on a near even keel. The great bow reared high the last to slip from sight at 1616. To starboard, the Nagato watched with silent foreboding."

After the futile attempt to rinse her, the NAGATO herself was shunned by the Americans who unable to board to examine her, had quickly lost interest. Though there was some talk of taking her in tow and sinking her at sea, the radioactivity made it unsafe to approach. All the while, the starboard list increased very slowly; three days later it had only reached eight-degrees. This was still so gradual that most observers now expected her to survive. To be sure, this was somewhat embarrassing, for getting-rid of the NAGATO had been one of the test's unstated objectives!

On the morning of the 29th July, however, the situation had perceptibly changed. NAGATO still floated on almost even trim as before, but sat deeper in the ocean. The stern seemed lower and the blue seas of Bikini now were washing over part of the main deck on the starboard side, particularly at frame 200. The waves were actually breaking at the base of the mainmast and hanger; the starboard list now ten degrees. The watching Americans kept an eye on her, but took no action to deter the sea's slow advance. However, all day,NAGATO remained in that state, and it seemed that she may well do so for many days. Apparently the flooding had equalized. Hovering astern, swung sideways like a waiting sword as if offering to be her second, the NEVADA also floated placidly, now the only close company.

Sunset descended on 29 July, covering Bikini and the wounded fleet with a velvet blanket of tropical dark lit only by the stars and the moon. It was then sometime after, under cover of darkness, that great NAGATO made her departure from the kin of men. As if troubled by her former adversary SARATOGA's passing in broad daylight before the gawking eyes of the world, the NAGATO chose her own time. Thus, unexpectedly, late that night or early morning of the 30th, NAGATO's starboard list must have suddenly increased, the stern dipped under, and she turned turtle, settling and gurgling down the short distance to the seabed. No one saw her go, no one knows the time. A samurai's hara-kiri.

Morning 30 July found the startled Americans and scientists gazing at an empty placid sea where NAGATO had been. They were morbidly surprised; after four days, they half-expected her to survive, but this much simplified things. An inspection of the site found her bottom up 120 degrees from upright, starboard side down, but the upturned keel still well below the surface level. It was later found the stern was broken where it had dug into the bottom first, and curiously that Yamamoto's famous haunt had survived, the pagoda bent to one side in the mud.

She lays there still today, fifty-seven years later. In death ironically accomplishing the immortality nearly all her comrades in the Imperial Japanese Navy failed to achieve. For today, along with the other illustrious victims of Bikini, SARATOGA, ARKANSAS, PRINZ EUGEN, SKATE, and many others, NAGATO can now be seen by those willing to make the trip and the dive, and which as part of an undersea park, will help the Bikinians earn back their lost stability. An atonement offering by the IJN, after a fashion, to the Pacific islanders whose lives it so helped to disrupt.

In this way, NAGATO indeed, has attained the samurai's dream:

"To die gloriously and live forever..."

@Anthony Tully 2003

Author's Note: Special thanks for assistance in suggesting and assisting the research for this article to Mr. Sander Kingsepp of Estonia. Thanks also to Mr. Bob Hackett whose work on the NAGATO trom allowed the clarification of chronology and certain events in NAGATO's life.

Note 2: Post-War, the Naval Technical Analysis team analyzed the damage to NAGATO, and concluded that the bomb that demolished the pilothouse was one, not two 500 pound SAP. The damage was apparently inconsistent with a double hit.

Note 3: Mention is made that a boiler "blew out" on NAGATO's last voyage off Eniwetok. If so, it means she began the voyage with five boilers operable. It is unknown which of the inoperable boilers was involved.

Sources: