Discovery of Imperial Japanese Navy Submarine

August

1st 2013

On August 1

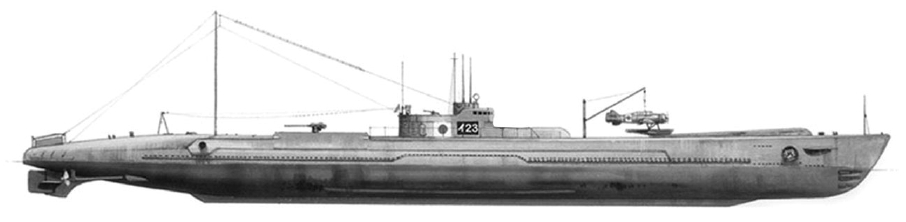

It was clear during the survey that the newly-discovered IJN Submarine had the capacity of launching aircraft (watertight hangar infrastructure, launch ramp, recovery crane) from its deck. This report summarizes the evidence supporting the identification of this discovery as the Sen Toku class I-400 and not the B1-class I-23 (alternate undiscovered IJN submarine also aircraft-capable lost somewhere in the area). This was the first submarine of this significant type of undersea craft, which at the time were the largest and longest-range submarines in the world.

The large I-400, with its extended range (37,500 nautical miles) and ability to launch three M6A1 Seiran strike aircraft, was clearly an important step in the evolution of submarine designEven though its operations were (fortunately) curtailed by the end of armed conflict. The innovation of air strike capability from long-range submarines truly represented a tactical change in submarine doctrine. The history of submarine design had been almost exclusively dedicated to sinking surface ships (and other submarines) by stealth attack from underwater. Following the war, submarine experimentation and design changes would continue in this direction, eventually leading to ballistic missile launching capabilities. The wreck of the I-400 therefore is archaeologically significant due to the design features associated with its large watertight hangar and Seiran strike aircraft launching capability.

The significance of the I-400 wreck site, though, is not only due to this technological innovation. Maritime heritage resources, when properly studied and interpreted, add an important dimension to our understanding and appreciation of our shared maritime legacy, to events that made us who we are today. NOAA's Maritime Heritage Program promotes maritime heritage appreciation throughout the entire nation. HURL's many discoveries in this field have been particularly helpful in achieving NOAA's heritage resource goals. The discovery of the I-400 is the latest example of this. These historic properties in the Hawaiian Islands recall the critical events and sacrifices of World War II in the Pacific, a period which greatly affected both of our nations and shaped the Pacific region as we now know it. Our ability now to interpret these unique weapons of the past and jointly understand our shared history of triumphs and tragedies is truly a mark of our progress from animosity to reconciliation. That is the most important lesson that the site of the I-400 can provide today.

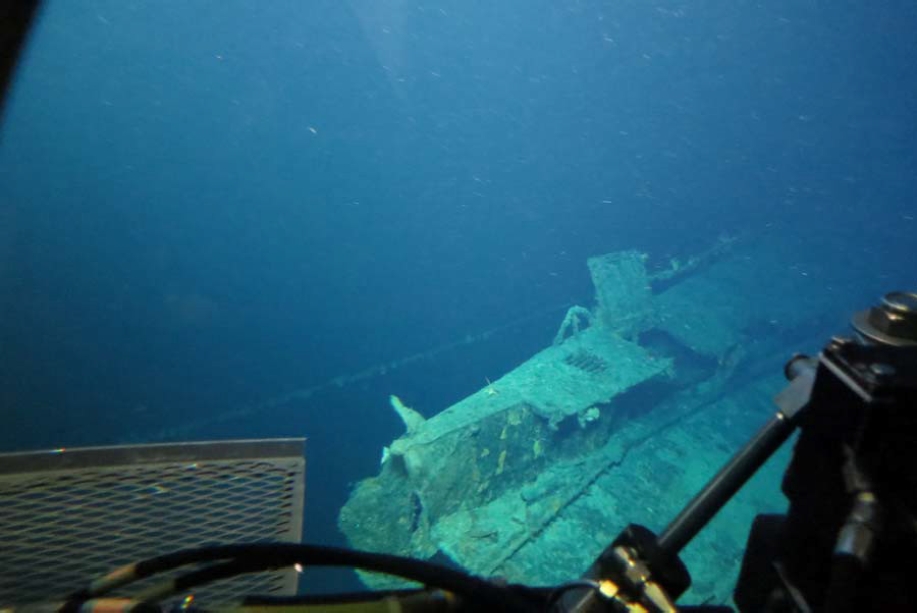

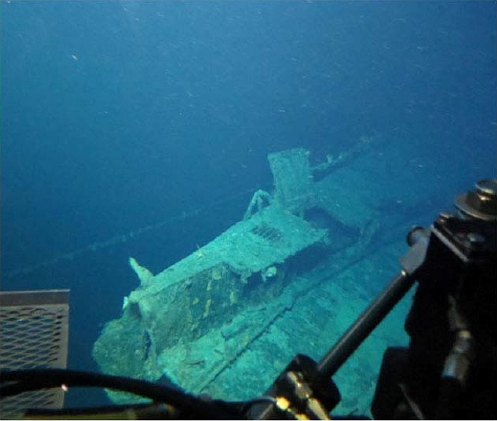

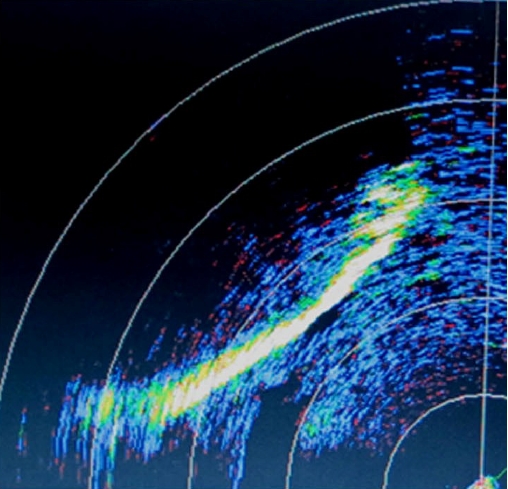

The mission for August 1st was to investigate two anomalies from high resolution seafloor mapping surveys that HURL had identified as targets of interest. The targets were 6 miles apart so the submersible would have to surface after identifying the first target then be transported to the second target. The first target turned out to be an IJN Submarine with the capacity of launching aircraft (hangar infrastructure, launch ramp, deck crane) on deck. Pisces V was guided to the target by surface tracking and acquired a strong sonar target indicating a large vessel 100m away. As Pisces V approached the target a large diameter cable was detected coming off the bottom and disappearing in mid water in the direction of the wreck. Pisces V followed the cable up to a point where it was draped over the wreck. The submersible crew had the first glimpse of the bow of a submarine.

As Pisces V moved up over the deck the crew found an aircraft launching ramp. Moving aft the crew discovered that the upper superstructure, hangar and conning tower were missing. The next identifiable features were the after deck gun, access hatch and stern. Pisces V dropped to the seabed to inspect the stern then moved up over the top of the stern to make a closer inspection of the deck gun and after hatch. After surveying the stern Pisces V moved forward to the bow and discovered that the catapult launch ramp was twisted and bent over the port side of the bow. The crew observed what appeared to be the end of the bow with the very tip torn off. Pisces dropped down to the seabed off the bow and discovered the end of the bow had torn off and that a section of the bow was lying on the bottom.

|

| |

| Stern. Rudder, dive planes, and screws. | Aft hatch and deck gun. | |

|

| |

| Twisted launch ramp hanging over port bow. | Torn off bow with torpedo tubes and launch ramp. |

The crew concluded that they had discovered the wreck of the I-400 due to the similarities of the after deck gun, after hatch, and launch ramp to the I-401, discovered by HURL in 2005. Pisces V moved 400m to the North to investigate another target to see if it was a section of the conning tower that might better identify this submarine as the I-400. The side-scan target was an old coral reef formation. The submersible crew decided to surface and move to the second major target while there was still time to conduct another dive. Pisces V surfaced, was recovered and transported to the second dive site where it launched to investigate the other target, which turned out to be the IX-71, an auxiliary cable laying ship used by the Navy during the war.

Further examination of the information gathered during the dive on the Japanese submarine raised questions as to whether or not it was actually the I-400. The only other submarine it could possibly be was the I-23. The I-23 was a 356ft B-1 type submarine. The I-23 also had a catapult launch ramp and an after deck gun. The I-23 was deployed on a mission to Oahu in February 1942 to provide support for a planned second attack on Pearl Harbor. The mission objectives were to remain undetected 10 miles south of Pearl Harbor, report on weather conditions and ship traffic and act as an air-sea rescue capability after the attack if needed. The I-23's tabular history as per Hackett/Kingsepp states that the I-23 reports her position south of Oahu on February 14, 1942, officially beginning her mission, and then is never heard from again. If the Japanese submarine discovered on Pisces V dive #815 is the I-23 then it is no longer a submarine sunk as a target after the war, but a wartime casualty and a war grave for 96 Japanese sailors. The decision was made to hold off on the announcement that the I-400 had been discovered until further closer examination of the wreck could be done.

A number of factors led to the possibility that this submarine could be the I-23.

Both submarines carried a catapult launch ramp and a similar after deck gun.

The length of the multi-beam target and the sonar target from Pisces V was too short to be the I-400. The target length was closer to the length of the I-23.

The position of this submarine was 2 miles away from the recorded Navy position for the sinking of the I-400.

The damage to the submarine was inconsistent with the damage observed on the three other Imperial Japanese submarines discovered by HURL. The I-401, I-14, and I-201 were part of the same group of five submarines captured at the end of the war and brought back to Pearl Harbor together with the I-400 and I-203 and eventually sunk as targets by the Navy off of Barbers Point.

The I-401, I-14, and I-201 were discovered with the bows missing forward of the conning tower but with the conning towers intact on all three submarines. The bow section of each wreck was about 200m away from the main hull section.

|

| |

| I-401 numbers on conning tower | I-401 conning tower | |

|

| |

| I-14 numbers on conning tower. | I-14 conning tower. | |

|

| |

| I-201 numbers on conning tower. | I-201 conning tower. |

The I-400, I-401, I-14, and I-201 each took torpedo hits forward of the conning tower. When the I-401 sank the 150ft long hangar came out of the main hull when the bow broke off but left the conning tower and main hull intact. When the vessel broke apart it left a 250m debris field between main hull and bow. There were no signs of implosion damage.

The I-14 also had a 200m debris field between bow and main hull but the hangar remained intact in the main hull. There were also no signs of implosion damage.

The I-201 bow was also about 200m from the main hull with a clean break that did not have an extensive debris field between main hull and bow. There were also no signs of implosion damage.

The hull of the submarine discovered on August 1st 2013 is intact from bow to stern. The whole superstructure is missing and there are signs of massive implosion damage. These conditions contributed to the consideration that this submarine could be the I-23.

|

| |

| Implosion damage on stern of new submarine. | Hull implosion buckles deck on new sub. |

Since there was no reported anti-submarine warfare action off of south Oahu during the time the I-23 was on station to support this important mission it is most likely that it was lost due to an operational failure. This contributed to our consideration that this submarine could have been the I-23. An implosion could have caused enough damage to destroy the superstructure.

A second dive was planned to do a more detailed survey of this wreck to better determine its identity. HURL ran out of time before the dive could be organized.

At the time of the discovery of what became referred to as the "Mystery Submarine" HURL was involved in diving operations which began in July and ended on September 1, 2013. Diving operations required support seven days a week and left little time to dedicate to further research to try to identify this submarine using the survey information from the discovery dive.

Once diving operations were over we conducted a more detailed review of the survey information and historic documentation. The following is the result of that review.

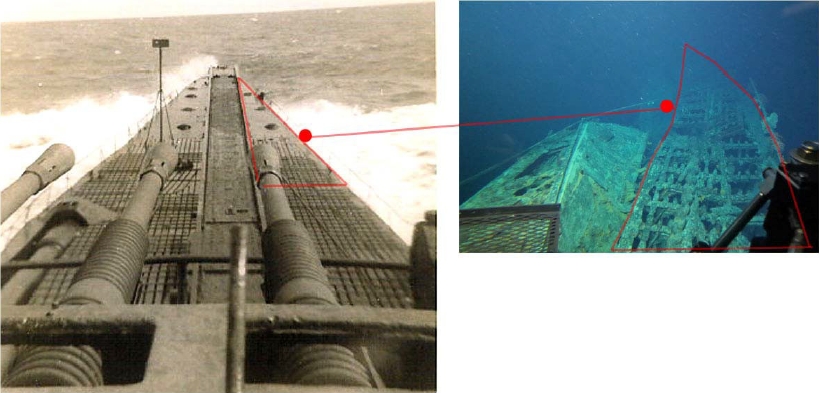

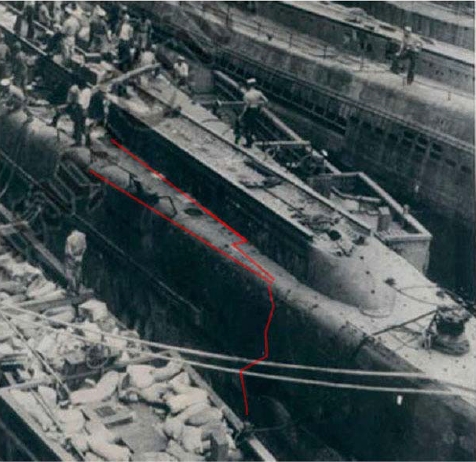

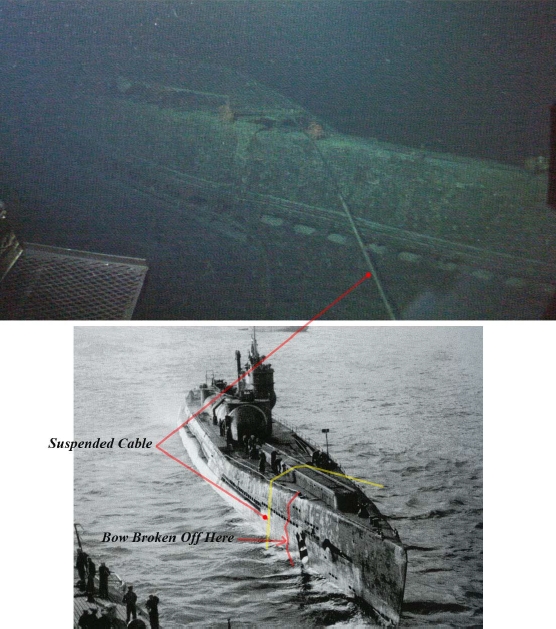

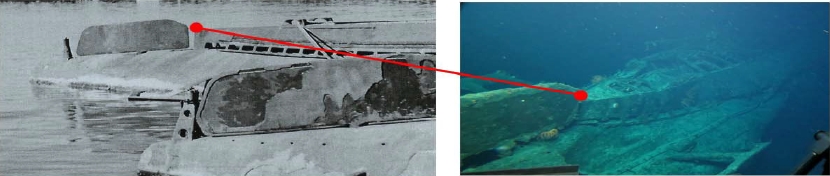

The length of the vessel was a major factor in suspecting that this submarine could be the I-23. What appeared to be the tip of the bow is actually one half of the starboard side deck of the I-400 that was alongside the launch ramp.

What initially appeared as the end of the bow is actually about 50 feet back from the tip of the bow.

This image shows where the port side of the bow broke away with the launch ramp and left the starboard side of the main deck. Note the triangular bracket next to the vent.

|

| |

| I-400 | Starboard bow section where bow broke off |

The I-400 took a torpedo hit on the starboard side of the bow which would account for this damage.

This would explain why the side scan image was closer to the length of the I-23.

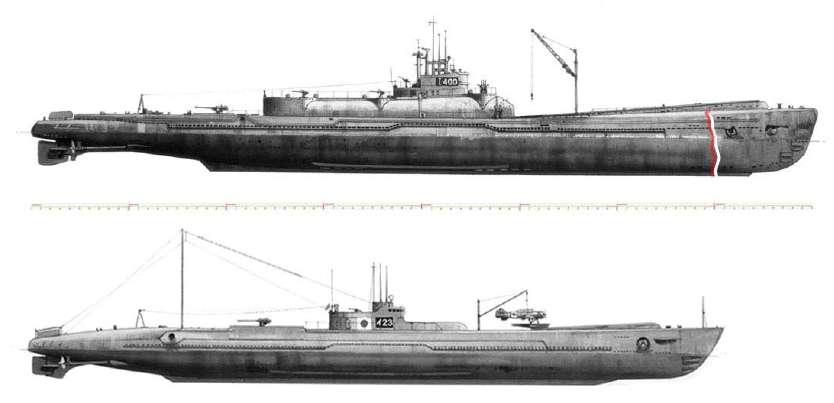

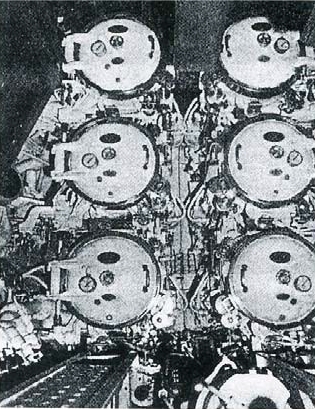

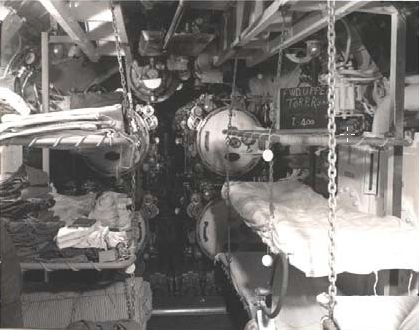

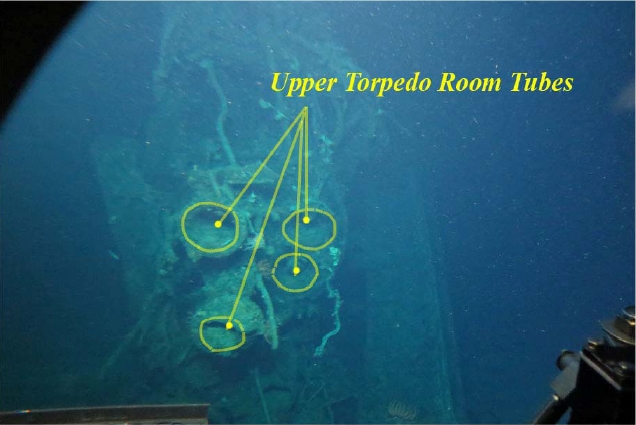

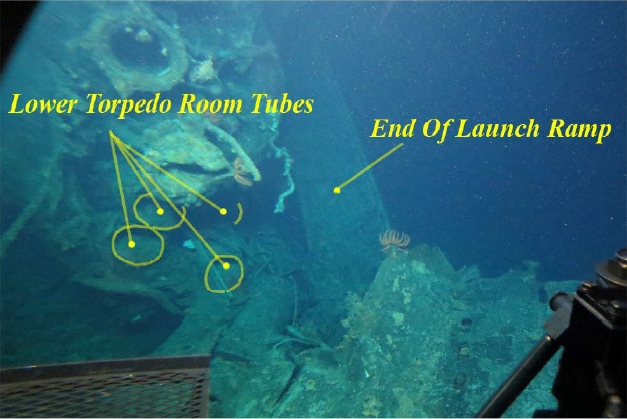

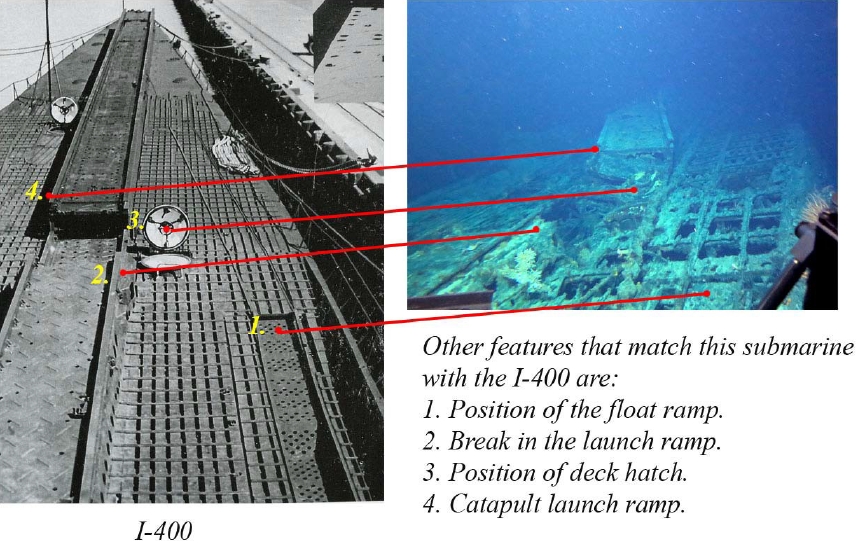

Another feature that matches this wreck with the I-400 is the number of torpedo tubes. B1 class submarines like the I-23 had 6 torpedo tubes in one torpedo room. I-400 class submarines had 8 torpedo tubes with 4 in an upper torpedo room and 4 in a lower torpedo room.

|

| |

| B1 Class submarine with 6 torpedo tubes. |  | |

| I-400 upper and lower torpedo rooms with 8 torpedo tubes. |

The inspection of the bow damage during the survey of the submarine shows what appear to be 8 torpedo tubes.

The end of the launch ramp is hanging down over the port side of the hull still attached to the end of the bow.

Another image showing the float ramp and space in the launch ramp.

|

| |

| Another feature that matches this submarine with the I-400 is the position of the deck crane on the port side of the deck. |

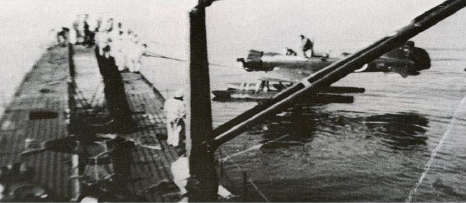

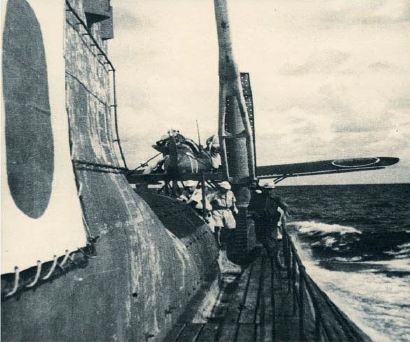

The deck crane on the B1 class submarines was mounted on the starboard side.

|

| |

|

|

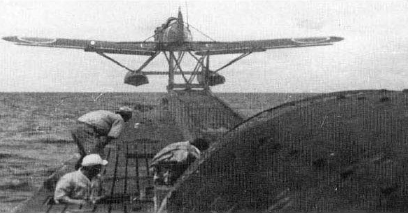

Here are some historic images that show aircraft launch and recovery operation from B class submarines that show the deck crane position on the starboard side.

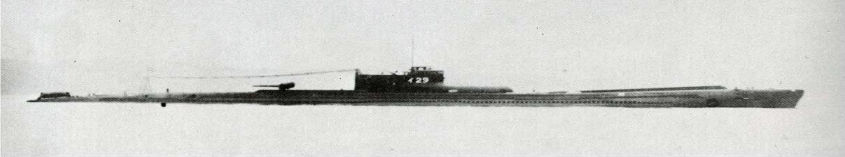

B1 Class Stern |

The B-Class submarines did not have the raised after deck

that ended in a point just forward of the upper rudder as did the I-400

class subs. This feature is prominent on the wrecks of the I-401 and the newly discovered wreck. |

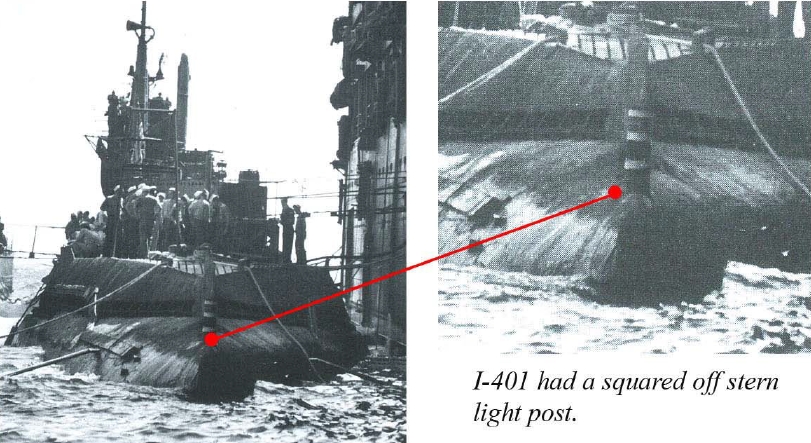

Although there are many features that match this wreck with an I-400 class submarine, there is one feature that positively identifies this submarine as the I-400.

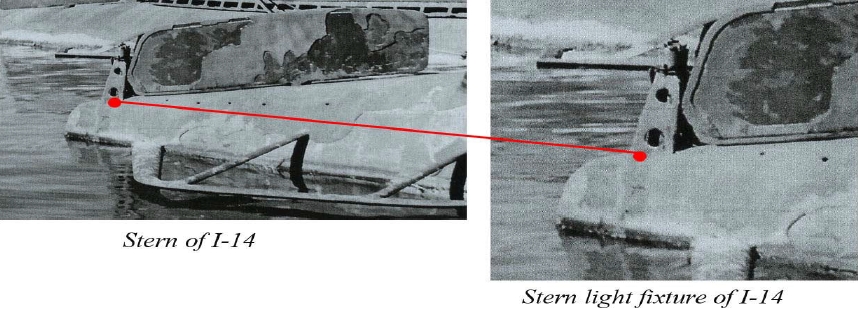

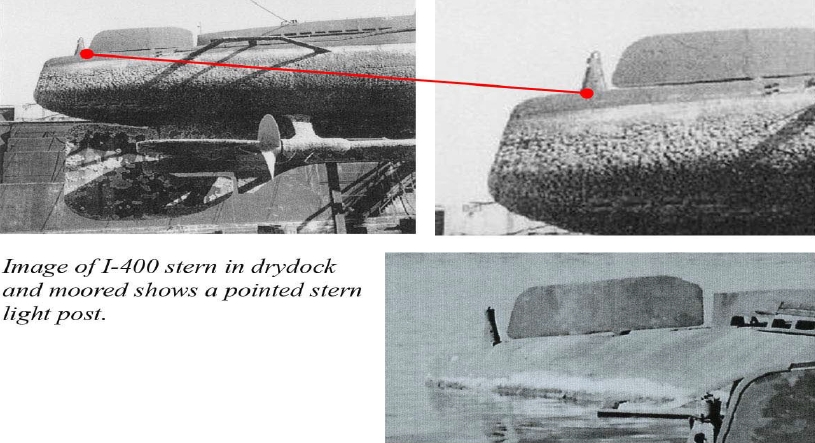

Each one of the Imperial Japanese submarines discovered by HURL off South Oahu had different fixtures for the stern running light.

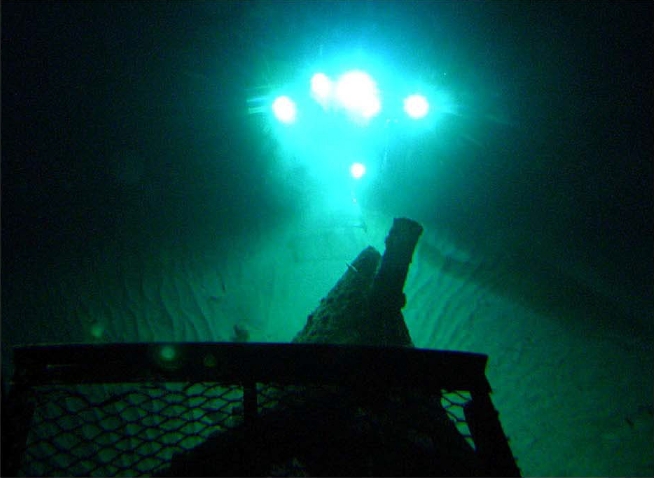

Image from Pisces IV over stern of I-401 with Pisces V on bottom backlighting the squared off stern light post of I-401.

The detailed review of this survey concludes that this newly discovered Imperial Japanese Navy submarine is the wreck of the I-400, but what happened to the aircraft hangar and conning tower?

As Pisces V moved from bow to stern we passed over what appear to be the cradle supports for the hangar.

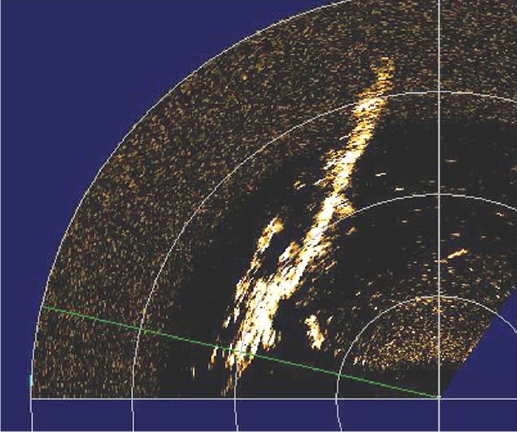

It appears the hangar and upper deck structure with conning tower separated from the main deck as the I-400 descended to 562m. The Pisces V crew did not encounter any debris field as we approached the wreck from the south or when the Pisces V moved from the wreck to the north to investigate the other side scan target. The sonar image out to 100m was clear of any other major targets that could have been debris from the superstructure. It is possible the remains of the superstructure could be next to the sub on the starboard side.

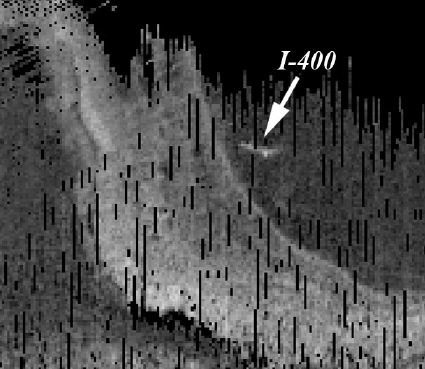

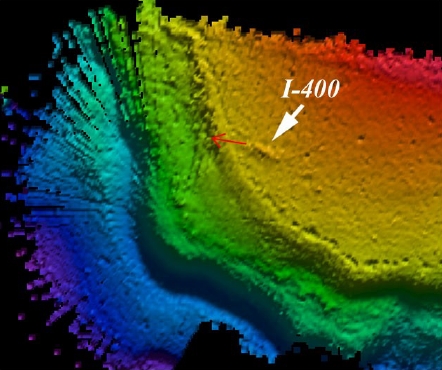

The sonar image of the I-401's main hull, which separated from the bow just forward of the conning tower shows a well defined line along the hull. The poor sonar image taken down slope of the I-400 shows a bulge that could be the remains of the conning tower. Only another detailed survey dive can tell for sure.

The other possibility is that the sealed hangar with superstructure separated from the main hull as the I-400 sank and drifted far enough away from the wreck that it did not leave a debris field.

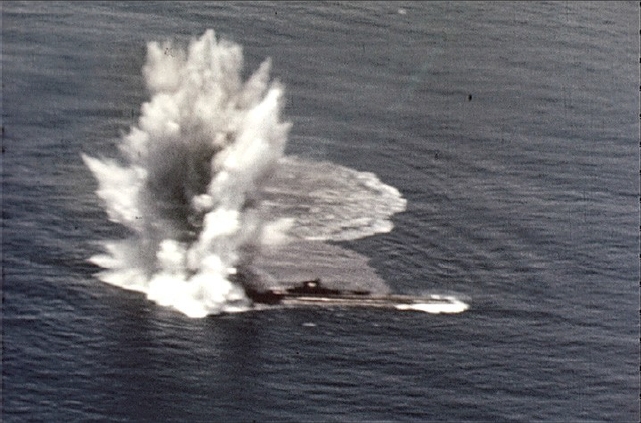

|

| |

| First torpedo hits just forward of conning tower and detonates the second torpedo before it hits the I-400. | I-400 from the port side after the first torpedo hit. | |

|

| |

| I-400 from port side after second torpedo hit on bow. | I-400 from starboard side as it slowly settles by the bow showing conning tower, hangar and upper decks still intact. |

The shock and impact damage from 3 torpedo detonations could have weakened the structural integrity of the vessel enough that the buoyancy from the 115ft long hangar caused it to break away from the hull as the I-400 sank. The hangar with conning tower and upper deck attached could have drifted away from the wreck and ended up down slope to the southwest.

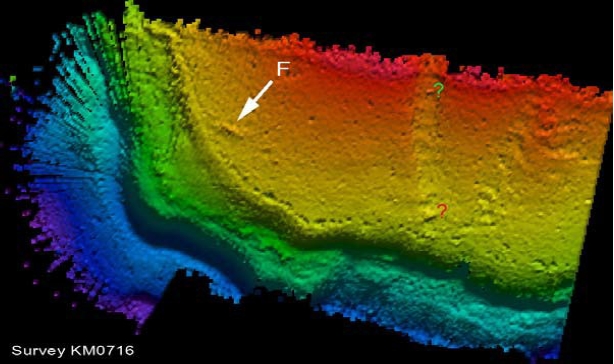

|

| |

| I-400 on backscatter survey | Hangar with conning tower could have landed on the bottom over the edge of the shelf in rocky terrain. |

The multi-beam survey data shows other possible targets along the base of the shelf that are most likely rocky outcrops but could be hiding the remains of the hangar and conning tower of the I-400.

Where is the I-23?

It is unlikely the I-23 would have abandoned their mission and departed Oahu without contacting the Japanese Naval Command. The location of the I-23 and final resting place of the 96 Japanese sailors aboard is probably still off of South Oahu somewhere.

The Hawaii Undersea Research Lab will continue to work closely with NOAA's Maritime Heritage Program to investigate other targets whenever possible to try and locate this important historical submarine and the remains of her crew.

Carpenter, Dorr and Polmar, Norman Submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy Naval Institute Press, 1986

Fabian, Gary (UB88 Project) Multibeam chart preparation and analysis

Hawaii Undersea Research Lab Video and photo surveys for Submersible dives: P4-136, P4-208, P4-209, P4-210, P4-211, P5-815

Hackett, Bob and Kingsepp, Sander Sensuikan! http://www.combinedfleet.com/ Tabular Records of Movement (TROMs) for IJN Submarines I-400 & I-23, Sen Toku Class Submarines, B1 Class Submarines.

Kelley, Chris (Hawaii Undersea Research Lab) Side scan chart preparatation and analysis

Naval Heritage and Historical Command Images of the sinking of the I-400, I-401, & I-14 Captures from historic video footage May 28 & 31 and June 4, 1946

Nila, Gary, Sakaida, Henry, & Takaki, Koji I-400 Japan's Secret Aircraft-Carrying Strike Submarine. Hikoki Publications Ltd. 2006.

St. Mary's Submarine Museum, St. Mary, GA, Donated Photos from Submarine Veteran

Stille, Mark and Bryan, Tony Imperial Japanese Navy Submarines 1941-45. New Vanguard 135. Osprey Publishing Ltd 2007.

University of Hawaii R/V Kilo Moana Multibeam Survey KM0716 Kongsberg EM1002 August 30, 2007

Unknown Japanese Author(s) IJN Japanese Submarines. Part 1 The Maru Special #31, 1979.

Unknown Japanese Author(s) Japanese Navy I-Boats I-400 & I-13. Gakken Pacific War Series #17, 1988.

Unknown Japanese Author(s) I-Type Submarines, Volume 15 of the great 3D CG Futabasha Super Detail series. Soyosha Publishing Firm of Tokyo

Van Tilburg, Hans (NOAA Marine Sanctuaries) Images photographed through viewports on submersible dive P5-815