RISING STORM - THE IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY AND

CHINA

1931-1941

© 2012 By Anthony Tully, Bob Hackett and Sander Kingsepp

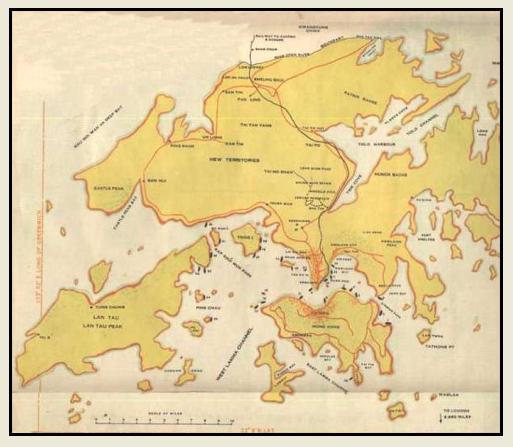

But one thing had always evaded even the British Empire's control, and that was the weather and sea. For that however, the authorities could at least seek to warn, and had established an Observatory for that purpose. Now at 1520 that station broke out and hoisted the requisite and dread signals that a powerful typhoon had been reported out to sea, rumbling westward toward Hong Kong island. It was a No.8 Storm signal, one of the most severe, and the packed shipping was advised to batten down and rig accordingly with all due precautions. The typhoon had formed off Luzon and was advancing northwesterly at a rate of 20 mph. Known as "taifeng" (disastrous storms) to the local Chinese, the power of such was well respected and feared, but their course could be hard to forecast.

The situation bore an ominous resemblance to a previous great typhoon that had wrecked Hong Kong in another September in the first decade of the century. On the night of 18 September 1906 a typhoon had hit Hong Kong harbor directly, reportedly sinking or wrecking thirty-one vessels including the French destroyer FRONDE, and annihilating thousands of sampans and junks. As many as 10,000 had been reported lost, with damages of twenty million dollars, particularly in the Kowloon district. However, in 1906 there had been only twenty-minutes warning before the typhoon struck -- this time there was more warning, hours, instead of minutes. Which was fortunate, for 1906 notwithstanding, the typhoon that now slammed into Hong Kong was believed the largest recorded to that time. Unfortunately, despite the afternoon alert, it was later than it might have been. The observatory had actually learned of the typhoon in late August and been tracking it, duly noting its arrival in the Balintang Channel on 31 August, but as late as 1 September had thought it would pass well south of Hong Kong. Instead, at the last minute the storm changed course and drove straight toward Hong Kong Island.

It was the worst possible timing, for the harbor was unusually crowded due to the Japanese invasion of Shanghai, and many ships had taken up indefinite residence until the battle waned. Steamers were directed to move from Kowloon wharfs and sea into the - presumed - more sheltered area of the so-called Junk Bay (Cheung Kwan O) to the east where a large number of the famous floating dwellings of residents also stood. One by one the ships made the transfer, taking up new anchorage spots as nightfall descended and winds increased to a threatening gale force and beyond.

There was a catch-22:-- ships anchoring in Junk Bay were out of sight of the shore stations and thus could get few updates on the strength and position of the incoming storm. When the torrential rains of nearly 3 inches per hour blotted out all visibility, it was impossible to exchange information. Many captains said later they would have steamed out to take their chances in the open sea had they been warned of its intensity and direction change. As it was a group of large war and merchant ships attempted to ride out the storm with multiple anchors and lines run out in Junk Bay or the main harbor. Their names read like an international roster of the powers then contesting for control and influence over China and the Far East: ASAMA MARU, SCHARNHORST, TALAMBA, RAWALPINDI, CONTE VERDE, FENG LEE, CORFU, HZING PING, SHENANDOAH, TYMERIC and even warships like HMS SUFFOLK, DUCHESS and CORNFLOWER. What followed might remind the informed reader of the great typhoon off Samoa in 1889. Now, as then, a group of international shipping with very opposed agendas and interests were thrown into common cause as they sought to survive an even mightier and common adversary -- the sea unleashed. Nor was it simply a storm -- but a typhoon passing against a great anchorage, with a power whose figures still find standing in the record books.

Dusk came, with darkness made greater by the sweeping rains as the storm center and its wide eye spiraled westward toward China, grazing along Hong Kong Island's southern shore. Nonetheless, as late as 2230 the harbor swell was deceptively moderate and few suspected the imminent danger. Then at half past midnight the wind rapidly increased and storm surges began to sweep into Kowloon Bay. The hurricane-force winds -- for such they were -- increased to a banshee intensity in the hours that followed, blowing dwellings over like paper boxes and rolling and pitching steamers at their moorings where huddled in Junk Bay. Though the narrow Lyemoon Pass of Hong Kong's eastern entrance fortuitously somewhat limited the scale, the storm surge funneled through the southeastern quadrant and Tathong Channel, to crash into the squarish shaped bay.

The eye passed toward the mainland after midnight, but if anything, the typhoon seemed to get worse as the backside winds resumed. At 0100 epic storm surges more akin to tsunami - "the tidal wave that came from nowhere" as it was later called - began rolling in along the waterfronts. Ships started breaking adrift, swept and carried by spiralings of water out of Junk Bay and into the pass. One of the biggest casualties was the large Japanese liner ASAMA MARU. Along with many others, her moorings snapped under the titanic winds, driving the vessel into open waters and against others. Bearing down out of the gloom with all her lights with the appearance of "what seemed a small town" ASAMA MARU rushed toward the British TALAMBA's starboard bow. She struck with a tremendous crash, bursting the foc'sle deck and warping the bow. ASAMA MARU then grated along TALAMBA's side to amidships even crumpling her bridge before swirling clear again. TALAMBA, till then holding position, now had her own moorings snapped by the impact and also broke adrift. What followed was almost inevitable.

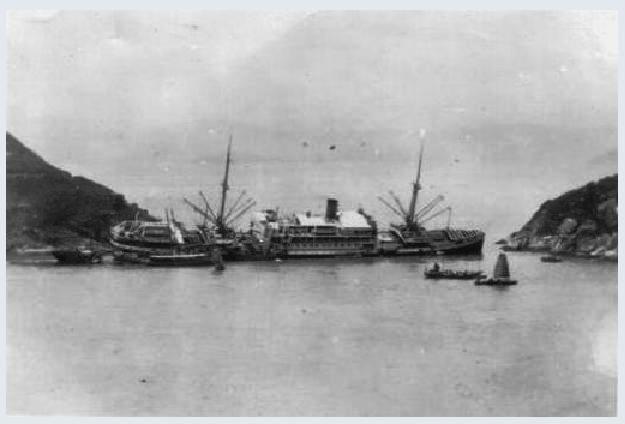

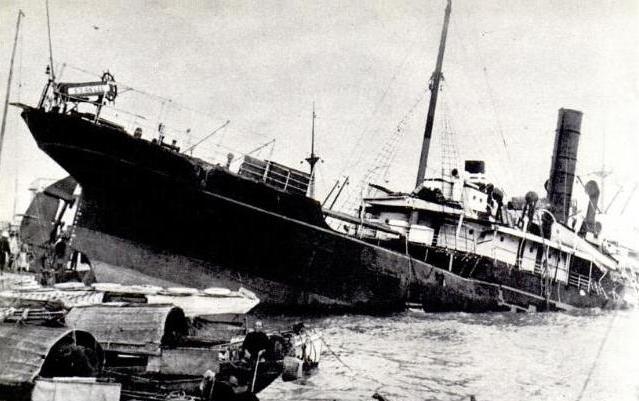

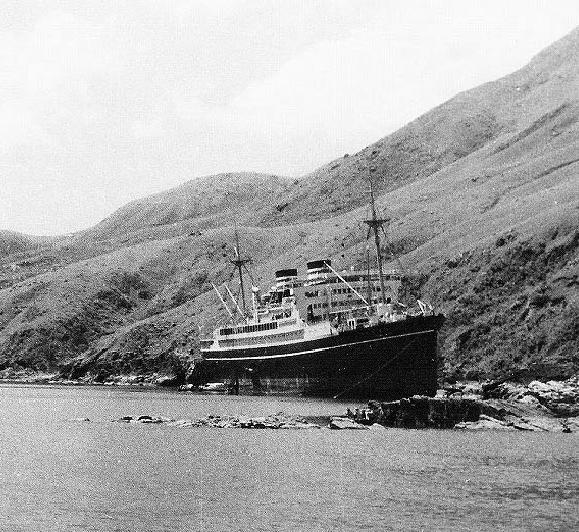

TALAMBA was now down at the bow and out of control. Within minutes she went slamming ashore, her port side driven right ashore by the pounding waves and screaming wind, and left with propellers and rudder high and dry, plainly visible. Grounded with bow awash and leaning starboard to seaward. ASAMA MARU had made a similar unwanted `landfall'. After grinding against TALAMBA, she continued haplessly adrift, only to be collided with in turn by the equally distressed Italian liner CONTE VERDE. Both vessels, each veterans of the China runs, then went hard ashore at Saiwan Bay at the eastern entrance of the harbour. ASAMA MARU grounded with port broadside to shore off Lyemun Pass, but on nearly even trim with a modest list of 6 degrees to port. She suffered little damage otherwise. CONTE VERDE ended up nearly the same nearby, but much higher out of the water, with screws and much of her red bottom showing dry. Kowloon area was no better; TYMERIC stranded listed acutely off the waterfront as did others. The Dutch liner VAN HEUTSZ (4,500 tons) had tried to shelter at the western end of the harbor with all anchors out. But she too was uprooted and then so firmly stranded off Green Island all 1,200 refugees from Shanghai had to be transferred ashore after weathering the horrifying night. The TANDA's (6,956 tons) passengers endured similar; their ship had broken adrift and they spent the night huddled in the dining room for safety on Captain Pilcher's orders. At dawn they found they had just missed going aground; the shore only 600 feet away.

Even the big warships did not escape unscathed. The British cruiser HMS SUFFOLK and destroyers DUCHESS and DIAMOND were weathering the waves successfully, only to - like TALAMBA and others - fall victim to those which did not. The 1,668 ton Chinese AN LEE came surging down against them, banging and bouncing along both ships sides in the swirls like some bumper car. The AN LEE itself then slammed stern first right upon the Hong Kong waterfront wharf.[Note 1] Nonetheless, the warships got off lightly. The German SCHARNHORST and British RAWALPINDI ( both fated to have military careers in the coming WW II - one as a Japanese CVE and the other as a brave Royal Navy merchant cruiser) also reported little damage. Sister GNEISNAU avoided any.

Around 0430 the barometer finally started to rise, indicating the storm was weakening, and by dawn the brunt of the storm had blown over, having lasted just over nine hours. Daylight revealed a scene of almost unimaginable devastation. Despite the carnage, as earlier as 9 A.M. a ferry got underway, to take stock and film the desruction. All throughout the harbor thirteen steamers lay either aground or half-sunk where they lay. Others drifted helplessly, as tugs sought to lasso them. Most incredible of all was the sight of big steamers literally driven onto the wharfs and docks. The storm surge had been calculated as having risen nearly 14 feet above normal tide of about 8 feet, and the force of the winds were so great that fishes were blown to the roofs of buildings 90 feet above the ground. Iron lampposts were folded over at nearly right angles. Floodwater had reached into the main city areas as far as famed Des Voeux and Nathan Roads. Records list from 28 to 32 ocean-going vessels - of a total of 92,000 tons between them - driven ashore or damaged in various degrees, with more than 1,800 fishing boats destroyed. Others were more fortunate, and reported no significant injury.

With such large ships being tossed around literally like bathtub toys, the devastation and havoc the huge storm surges wrought among the famous offshore floats, conjoined junks, and sheds is better imagined than described. Suffice it to say, the destruction rivaled any inflicted by the undeclared war then raging all around. When the weather cleared, the harbor had been all but swept clean of the picturesque dwellings. Their remains, along with several full size steamers, lay jammed and piled against the buildings and docks of the shoreline. Fires had broken out; one at Connaught Road for hours, gutting about ten major buildings. At the narrow Tolo Channel, the storm surge crested into a 30 foot tidal wave that funneled into the bottleneck and practically erased the fishing villages Sha Tin and Tai Po. The low-lying towns were engulged, the squatter dwellings and houses completely destroyed, and the wave washed away nearly a mile of the adjacent Kowloon-Canton railway on its embankment. An estimated 10,900 people lost their lives, a little over 1% of the entire Hong Kong population in 1937. For days after, bodies rising and drifting clogged the harbor. A large number of the people that perished had been living aboard the fishing boats and were drowned when capsized, unable to reach shoreline. Though the steamer skippers would later say they wished they had gone to sea, it proved little refuge either for those that were. Forty junks of the famed Aberdeen fishing fleet then at sea foundered outright, with only five survivors known out of some 450 aboard plucked from the waters five days later. The council of Canton was forced to put off its accustomed bickerings for ten days.

Reportedly the anemometer at the Royal Observatory of Hong Kong jammed when clocked winds at 150 mph and at the height of the storm the barometer fell abruptly by a full one inch. The hourly winds had been about 60 knots with gusts as high as 130 knots attained. At 0200 the Observatory had issued the No.10 and highest warning, but of course by then was as redundant to the ships as it was impossible to receive. In modern terms, therefore, the storm had achieved a Category 5. In the wake of the disaster all parties came together in a commendable display of international commraderie. Chinese soldiers descended from the shoreline to assist grounded vessels, while Russian and Chinese divers hurried down from embattled Shanghai to assess damage, and a British marine superintendent came from as far as Calcutta. Salvage often proves prolonged and difficult.

Despite "light damage" ASAMA MARU proved hard to refloat because of her size and weight. It was necessary to remove disesel engines among other things to lighten ship by 1,300 tons so she could be refloated and hauled off the sea ledge. Finally in March 1938 she came afloat, and after work there in Hong Kong to make her seaworthy, ASAMA MARU sailed to Nagasaki that same month for full repairs.(For details see ASAMA MARU TROM.) TALAMBA coincidentally had re-entered service that same mid-March of 1938, having been refloated earlier, in November, but proving a longer drydock job before she could sail home. She was fated to be among the ships picking up survivors when battleships HMS PRINCE OF WALES and REPULSE were sunk by the Japanese on 10 December 1941. The Japanese did not attack her during this mercy task, but ironically while serving as a hospital ship TALAMBA was bombed and sunk off Sicily by the Germans after returning to the Mediterranean theatre.

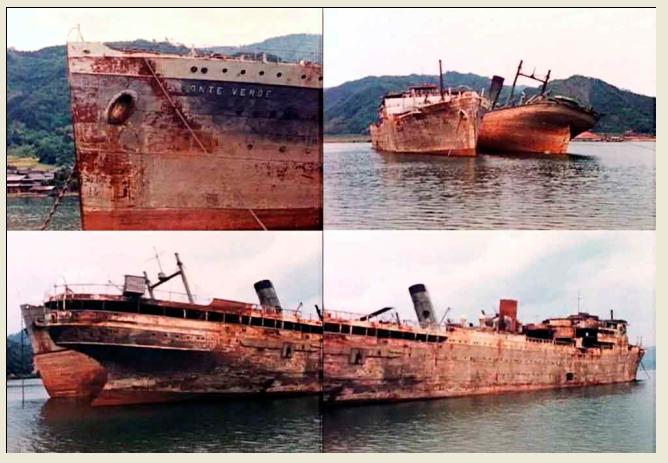

Though refloated the venerable Italian liner CONTE VERDE was destined to spend much of her future in these same water. She was at Shanghai when in June 1940 Mussolini declared war on France and formally joined Hitler in his war. There could now be no question of attempting to return to Italy, for the Royal navy blockade in the Mediterranean made this out of the question and as suicidal as it would be pointless. The CONTE VERDE was still at Shanghai when Japan opened the Pacific War in December 1941. She entered a holding state. What would now ensue is a series of episodes out an adventure novel. When Italy surrendered and broke from the Axis on 9 September 1943 CONTE VERDE was quietly scuttled and allowed to bottom in the Whangpoo Riber by her Italian Crew under the cover of the festivities and commotion of a banquet held aboard that night. The frustrated Japanese would not give up on her, and re-naming her KOTOBUKI MARU, set about to raise and restore her. For more details of this enterprise and a dramatic voyage see the TROM of KOTOBUKI MARU.

The Great Hong Kong Typhoon would temporarily unite the fates and concerns of the various rivals in the China theatre, but the moment of shared humanity against a common foe would prove extremely fleeting. There was to be one other major case of international cooperation at the end of the same year, but these would prove the exception, not the rule. In a curious after-note, LIFE magazine's coverage of the disaster mentioned that "with absolute impartiality another typhoon on Sept. 11 struck Japan, destroyed crops and shipping but did not seriously interfere with the war." The transitory moment of mutual drama and common cause was already fading and later that selfsame September would see some of the fiercest clashes between the Japanese and Chinese Navy in the conflict.

Further references for pictures:

http://www.merchantnavyofficers.com/typhoon.html.

LIFE Magazine, 4 October 1937 issue. pp 48-49.

-Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp and Anthony Tully